Valentine's Day is a time to celebrate romance and love and kissy-face fealty. But the origins of this festival of candy and cupids are actually dark, bloody — and a bit muddled.

Enlarge Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHulton Archive/Getty Images

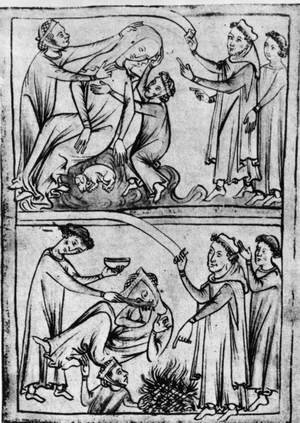

Enlarge Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHulton Archive/Getty ImagesA drawing depicts the death of St. Valentine — one of them, anyway. The Romans executed two men by that name on Feb. 14 of different years in the 3rd century A.D.

A drawing depicts the death of St. Valentine — one of them, anyway. The Romans executed two men by that name on Feb. 14 of different years in the 3rd century A.D.

Though no one has pinpointed the exact origin of the holiday, one good place to start is ancient Rome, where men hit on women by, well, hitting them.

Those Wild and Crazy Romans

From Feb. 13 to 15, the Romans celebrated the feast of Lupercalia. The men sacrificed a goat and a dog, then whipped women with the hides of the animals they had just slain.

The Roman romantics "were drunk. They were naked," says Noel Lenski, a historian at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Young women would actually line up for the men to hit them, Lenski says. They believed this would make them fertile.

The brutal fete included a matchmaking lottery, in which young men drew the names of women from a jar. The couple would then be, um, coupled up for the duration of the festival – or longer, if the match was right.

The ancient Romans may also be responsible for the name of our modern day of love. Emperor Claudius II executed two men — both named Valentine — on Feb. 14 of different years in the 3rd century A.D. Their martyrdom was honored by the Catholic Church with the celebration of St. Valentine's Day.

Later, Pope Gelasius I muddled things in the 5th century by combining St. Valentine's Day with Lupercalia to expel the pagan rituals. But the festival was more of a theatrical interpretation of what it had once been. Lenski adds, "It was a little more of a drunken revel, but the Christians put clothes back on it. That didn't stop it from being a day of fertility and love."

Around the same time, the Normans celebrated Galatin's Day. Galatin meant "lover of women." That was likely confused with St. Valentine's Day at some point, in part because they sound alike.

Monday, February 14, 2011

The Dark Origins Of Valentine's Day

via npr.org

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment